This part of the tutorial explains how to publish your vocabulary at a stable URI using RDFS/OWL. In order to make things easier, I’ll illustrate each step of this part of the tutorial with an example. The steps to follow are further described below:

1) Select the name of your vocabulary/ontology. Easy, right? In my case I want to publish an ontology encoding the workflow motif catalogue we describe in this paper, so the name I have chosen is “The workflow motif ontology” (wf-motifs to keep it short).

2) Select the proper URI to publish your vocabulary. Now that we know how we want to name our vocabulary, things start to get trickier. Which URI do we choose? How do we ensure that it is not going to change?

The URI you choose for your ontology should be permanent and defined in a domain you control. The rationale behind this is simple: imagine that somebody is reusing the concepts defined in your ontology and you change its URI. The person reusing your ontology will no longer know the proper definitions and semantics of the reused term.

Since I assume that most of the people reading this are not willing to pay for a new domain each time a new ontology is published, I recommend defining the URI of your vocabularies/ontologies in http://purl.org. PURL stands for “persistent uniform resource locator”, and they are widely used to give persistent URIs to resources. Once you register in the page, the process is really simple. You define a new domain, wait for the approval and create the URI for your ontology. In my case it is: http://purl.org/net/wf-motifs.

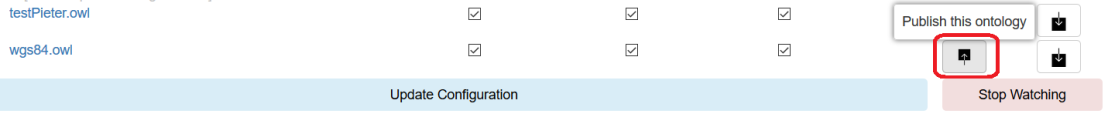

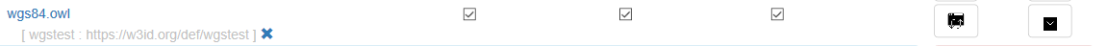

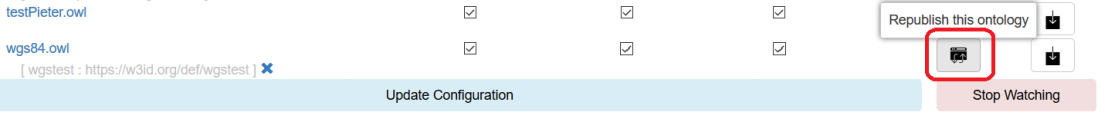

EDIT: If you are interested in having more control on your redirections, w3id is a better alternative to purl. Have a look at my post for more information on how to set it up.

Note 1: If you create the name under the /net/ domain things will go faster, since it is the default domain. Otherwise they’ll have to approve the domain AND the name of your vocabulary/ontology.

Note 2: Someone could argue that by speaking to the system admin of your enterprise/university you can obtain the vocabulary URI as well. However, depending on who you are and the ontology you are working on, the URI they suggest could be something like: mayor2.dia.fi.upm.es/oeg-upm/files/dgarijo/wf-motifs. This is perfectly fine, but this looks more like the place where my .owl will finally be stored. If my file has to be moved, my URI will change. Using purl ensures the URI will be permanent, and that I have control over it.

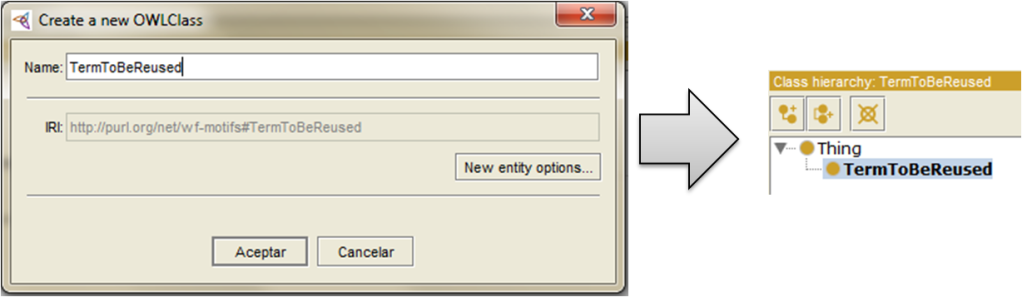

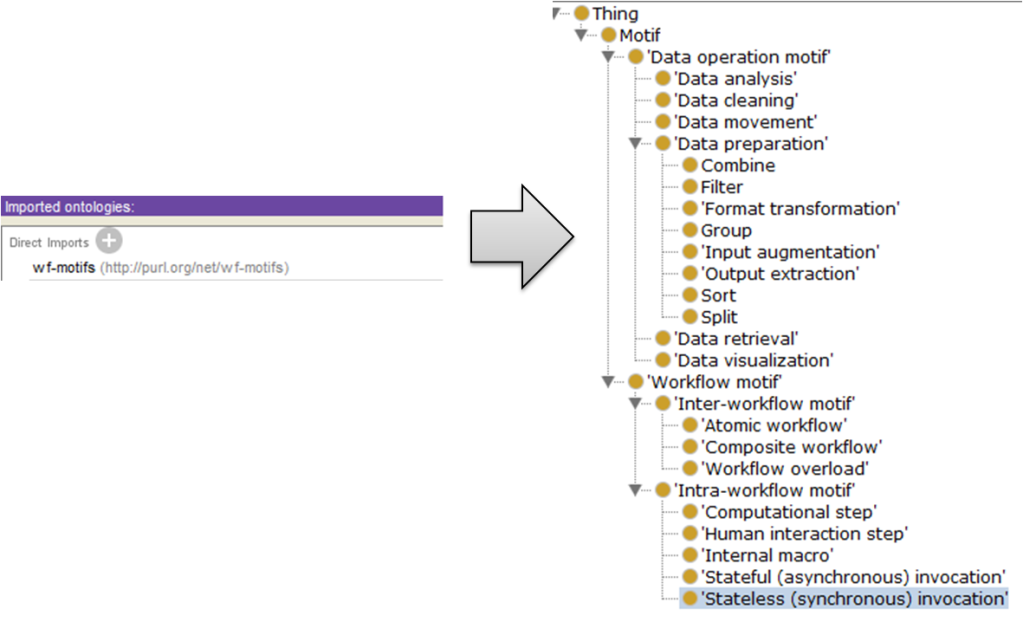

3) Create the ontology in RDF/OWL: There are several editors to create vocabularies/ontologies and their properties according to the W3C standards: Protégé, the NeOn Toolkit, TopBraid Composer, etc. The one I’m most familiar to is Protégé, which is free to install and use (they say that TopBraid is very good, but since the license is quite expensive I haven’t been able to test it). Once you have installed your editor you just have to change the base URI of the ontology (Ontology IRI in Protégé) with the one you registered as a PURL. Protégé will use a hash (“#”) by default to identify the classes and properties you declare in the vocabulary/ontology. You can use a slash (“/”) for this purpose as well.

Hash versus slash debate: There has been a long discussion regarding the usage of “/” vs “#”. If you are not sure about which one is the best for your vocabulary/ontology, here is a tip: if your ontology will be huge and will be divided in many different modules, use “/”. Otherwise use “#”. It is easier to set up and will make it easier to point to the right spot in the documentation.

Returning back to the example, this is how my ontology IRI looks like:

http://purl.org/net/wf-motifs#

and a sample class will be

http://purl.org/net/wf-motifs#Motif

4) Redirect your permanent URI to your vocabulary/ontology file. Once you are done editing your vocabulary/ontology, you have to host the .owl file somewhere. It is not important where you host it, as long as you know that it won’t be deleted. It’s fine if it gets moved, as long as you know where. In my case, I talked to the system admin and he stored the owl file here:

http://vocab.linkeddata.es/motifs/motif-ontology1.1.owl

Finally, we go back to the purl page and we add the basic redirection to the target URL we have just set up. The form looks like this:

Now whenever we enter the URI of our ontology, it will be redirected to the OWL file. Congrats!

Note: In my case http://purl.org/net/wf-motifs will take you to the ontology if you load it in Protégé and to the documentation if you load it from the web browser. I’ll explain how to achieve that in part 4 of the tutorial, so don’t worry for the moment.

Note: the steps I propose here are not normative. There may be other ways to achieve what is covered here. This is just a possible way to do it.

This is part of a tutorial divided in 7 parts:

- Overview of the tutorial.

- (Reqs addressed A1(partially), A2, A3, A4, P1) Publishing your vocabulary at a stable URI using RDFS/OWL. (this post)

- (Reqs addressed P2, P3). How to design a human readable documentation.

- Extra: A tool for creating html readable documentation.

- (Reqs addressed P4). Derreferencing your vocabulary.

- (Reqs addressed A1 (partially)). Dealing with the license.

- (Reqs addressed A5, P5). Reusing other vocabularies.